An A-Z of wine wouldn’t be complete without looking at rosé – for no other reason than to keep friends (who shall remain nameless and) who drink gallons of the stuff, happy!

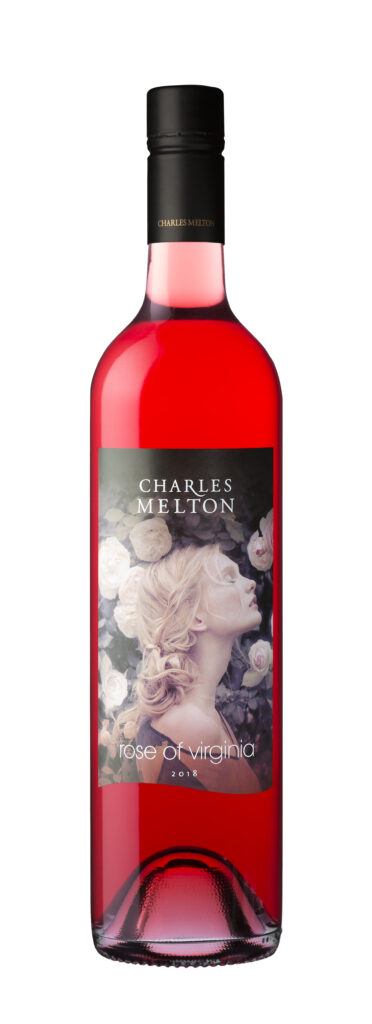

Rosé wines are made all over the world although it has for a long time been driven by the old world – France is a leading producer, particularly from the warmer southern reaches of the Languedoc, southern Rhone and Provence but not forgetting the Loire. It is also popular in Italy as Rosado and Spain as Rosato or Clarete (for pale and darker versions respectively). Some good examples can also be found in Australia (ie Charles Melton) and New Zealand.

Judging from sales, rosé is growing exponentially in popularity. Some of this is undoubtedly down to improving quality, but I suspect a lot is also to do with the fact that pink wines are just so instagrammable! You only need to check out social media to see it awash with images of millennials quaffing the stuff. Not discounting of course, the ‘Celebrity’ factor: “Brangelina” and Château Miraval anyone?

Before we look at how rosé wines are made, first a rhetorical question.

When you crush a red grape what colour is the juice?

Perhaps surprisingly to some the answer is not red. It is actually the same colour as the juice from a white grape. Why? Because the colour is not in the flesh of the grape, it is in the skins. The depth of colour is all to do with the amount of contact the juice has with the skins and to a lesser extent the thickness of the skins.

Did you know? There are exceptions to the above, these red wine grapes are known as “Teinturier” and have both a dark skin and dark flesh. Alicante Bouschet and Saperavi are examples of these.

The many faces of rosé

Rosé wines come in all styles and shades of pink, and from cloyingly sweet to dry, from the those with the merest hint of a pink hue (think the delicately coloured Provencal-style wines), to deeply-coloured semi-savoury wines as well as of course, sparkling wines. Yes, rosé offers all these choices and more.

How rosé wine is made

Saignée method – Meaning ‘bleeding’ or ‘drawing off’, as the name suggests, this process involved bleeding off a percentage of the juice early in the red-wine making process with juice left to macerate with the skins for between 6 and 48 hours before being bled off and fermented like a white wine at lower temperatures) to produce a rosé wine. A deeper colour would be obtained from a longer maceration.

Note – this process also means that the juice that is left in the tank for the red wine would continue macerating with the skins and because of more contact with the skins (less juice, more skins) it would produce a more concentrated red wine once fermentation was complete.

Direct pressing – rather than leave the juice in contact with the skins, the grapes are pressed immediately before being fermented as a white wine. This produces the most delicately coloured rosé wines as there is only minimal extraction of colour compounds from the pressing of the grape skins. A popular style in Provence and the Languedoc.

Then there is Blending – As the name suggests, this involves blending a percentage of red wine into a white wine to produce, yes, you’ve guessed it a pink (aka rosé) wine. Although this method is banned in Europe for the production of PDO still wines there is one exception – and it’s a big exception – Champagne. Yes folks rosé Champagne is made by blending! Note also that this method is allowed outside of Europe for still wines, particularly where vinification rules are, shall we say, less strict.

So that explains how rosé wines are produced, but grape variety is hugely important as it impacts both on the colour of the wine (thick skinned varieties naturally impart more colour) and flavour profile.

Grape varieties and flavour profile

Globally, pretty much all red grape varieties are used to make rosé although the best known include: Pinot Noir, Grenache, the two Cabernets (Franc and Sauvignon), Syrah, Merlot, Sangiovese and Zinfandel.

Each variety brings its own style and character to the finished wine. It’s also common to see blends of varieties used. The below is something of a generalisation but serves to give an example of the styles you can expect.

Fresh and fruity (dry): rosé produced from Pinot Noir, Grenache, Tempranillo, Sangiovese. Expect aromas of cherry, strawberry, cranberry and redcurrants.

Herbal and more savoury (dry): rosé produced from Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Mourvedre and Syrah. More blackcurrant notes alongside the red berries and tomato leaf, and even mint and red pepper notes.

Fruity, easy drinking (sweeter styles): rosé produced from Merlot, Grolleau (in Rosé d’Anjou) and Zinfandel. Less complex, lots of sweet red fruit, confected and possibly slightly jammy.

Top tip – if you prefer delicately coloured, fresh wines then you can’t go too far wrong with a Provençal rosé. If deeply coloured more savoury rosé is your thing – look for the wines from Bandol. Tavel and Lirac are also good wines to explore – usually quite deeply coloured, on the dry side with lots of fruit.

So the next time you pick up a bottle of rosé take a note of the grape variety and see if you can spot the differences in the flavours and style.

Next up “S” is for Sangiovese.