If pressed to name my favourite type of fortified wine it wouldn’t be Sherry, it wouldn’t even (despite loving these wines too) be Port, it would in fact be Madeira…and its not even close! I suspect Madeira is probably the wine most people pass over when perusing the aisles of the supermarket for a bottle of something fortified, which is a huge shame and the reason why the letter “M” is dedicated to the fortified wonder that is Madeira!

Disclaimer – I am not going to look at the viticulture nor all the history surrounding the crises that hit the industry in the mid 1800s, nor go into huge detail about the processes involved, rather this post is aimed at providing more of an overview of Madeira wines.

In order to understand how a hilly, wet, sub-tropical island located nearly 1000 kilometres off the Portuguese mainland in the wild windy Atlantic could be responsible for creating one of the true ‘classics’ of the wine world we need an (abridged) history lesson.

History

It’s fair to say luck played its part – by virtue of its geographical position, Madeira (the island not the wine) was a natural stopping off point for merchant ships travelling to the US, the Indies and beyond in the 17th Century, with vessels stopping off to pick up wine for trade as well as using the casks as ballast. In order to ensure the wine didn’t deteriorate on the long journey across the tropics, they were fortified with brandy or alcohol distilled from cane sugar.

It was during one such journey, legend has it, that a cask of wine was accidentally left onboard and only discovered when a ship returned to Madeira*, to the surprise of all, this ‘stowaway’ cask tasted incredible. This is how the term ‘Vinho da roda’ (return trip) – as the wine became known, was coined.

*The reality was probably more economic, that unsold wine was returned to producers’ but I prefer the other story!

No one understood why, but exposing the wine to excessive heat and movement during the sea transport transformed it, this oxidative exposure combined with extremes of heat producing flavours of caramel, dried fruits, coffee and lots of sweet spices. So popular was the style, that the wines continued to be aged this way until the 1900s when the realisation dawned that it simply wasn’t economical to bung wine onboard ships and wait for their return from the tropics – leading producers to try to creating a process that would artificially replicate the conditions without the wine having to leaving the island.

Did you know? Madeira was so popular in the Americas that it was drunk to toast the US Declaration of Independence in 1776.

Production

This can get a bit technical so this is just a very quick overview. Depending on the style of wine required, grapes will either be fermented on their skins or off skins, with fortification (in the form of rectified grape spirit) added either during the fermentation (which artificially stops fermentation and leaves high sweetness levels in the finished wine) or after fermentation has completed in which case the wine will be on the drier side.

The Madeirization process (as it is known) follows two basic principles, either:

Estufagem (Estufa means hot house) – the artificial heating of the wine in large concrete or steel tanks for a minimum of 90 days at 45-50oC. The wine is then rested before being bottled between 2 and 3 years after harvest. This method is generally used for the most basic wines (usually made fromTinta Negra) that are bulk produced and the wines can tend towards burnt caramel aromas. Some producers have adapted this process making it gentler (lower temperatures, longer ageing times) and use it for higher quality wines.

Canteiro – a process that relies on the natural power of the sun. Madeira is scorching in the summer, and this process involves the wine being placed into wooden pipes/barrels and stored in lofts over a period of years, where the sun heats them naturally. Over time the pipes will move to cooler parts of the loft where more gentle ageing occurs. This process is generally used for the finest wines made from the ‘noble’ varieties (see below).

Note – all wines will be a blend, the heating leads to evaporation, meaning pipes will need to be topped up during the ageing process.

The grapes and their wines

Tinta Negra (red variety) – more of a workhorse grape, making up the majority of plantings on the island, used predominantly for the cheaper Madeira made using the estufa process. Wines will usually be labelled by style ie dry, medium dry, medium sweet and sweet/rich. Usually released after only 2-3 years, these can include the term ‘Finest’ on the label which is slightly ironic!

Top Tip! – Beware when a label says dry, don’t expect bone dry like a normal wine, it just means it’s a drier style of Madeira.

Then we have the ‘Noble’ grapes (the four below are all white varieties), these are used for the best quality Madeiras and will be varietally labelled:

Sercial – pale in colour and the driest of Madeira styles. Wines made with this variety will have almond and citrus notes combined with a searing acidity and a hint of salinity.

Verdelho – medium dry these wines tend to be more rounded with honeyed notes, dried fruits and hints of caramel, developing a smokiness with age.

Bual – Dark brown in colour and much richer in style. Medium sweet, and fuller bodied with deep flavours of raisins, coffee and molasses alongside the caramel notes.

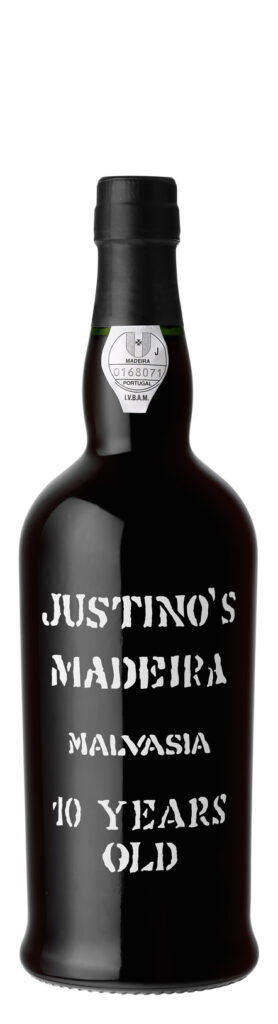

Malvasia (Malmsey) – the sweetest, richest style although slightly lighter in appearance than Bual. Hugely aromatic, walnuts, caramel, dried fruits, coffee and spices.

I enjoy all styles, but if your preference is usually for a rich super sweet sherry (like a PX) then I’d suggest you look for Malvasia (Malmsey). On the other hand, if you like a drier style with more citrus and nutty notes then Sercial may be more your bag.

Labelling and Identification of age

There are a confusing array of terms used on labels, the below is a snapshot of some to look for (this list is by no means exhaustive):

- An indication of year ie ‘Vintage’/’Frasqueira’ (a minimum of 20 years ageing)

- An indication of age, where the number of years shown is the average age of the blend:

- ‘Reserve’ (5 years old) – usually Tinta Negra dominant blends

- ‘Special Reserve’ (10 years old)

- ‘Extra Reserve’ (15 years old)

- You may also come across bottles indicating a specific year

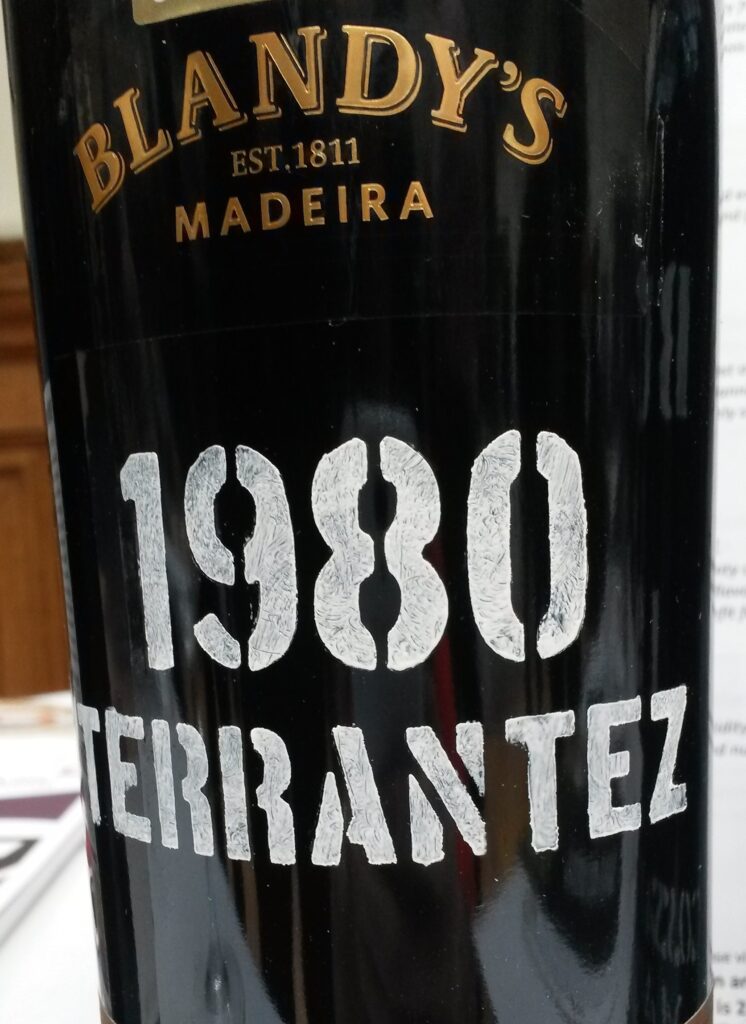

I was very lucky recently to taste a Terrantez from the 1980 vintage. This grape is also a ‘noble variety’ but is rarely produced these days as so few vines remain, however it is possible to lay your hands on some wines that are 40 or 50 years old. The one I tasted from 1980 was so fresh, vibrant and concentrated, you could almost have believed it had only just been bottled. Absolutely stunning.

Ultimately this I think is the key to Madeira and what sets it apart from all other wines – because of the processes the wines undergo and because of the naturally high levels of acidity all the grapes grown on Madeira possess, these wines age brilliantly, and above all, are virtually indestructible. Once opened, they can last months, possibly even years…providing you can keep your hands off them once opened that is!

Producers to look for:

Henriques & Henriques (H&H), Blandy and Justino’s can regularly be found on the High Street and offer tremendous value for money for the quality.

I will be looking to include one in my Christmas wine selection to keep an eye out nearer the time, they really are worth the effort.

We are now halfway through the A-Z of wine, next up “N” is for Natural Wine….stand by for a very divisive subject!