As a precursor to the release of the next Wine Demystifier Wine Club case, which will feature ‘Wine Blends’, I have put together a 101 on ‘Blends’, by which I mean a blend of more than one variety as opposed to the blending of different vats and barrels of the same grape variety – which incidentally is almost always done!

Undoubtedly there are many terrific wines made from single varieties, but why are many of the wine world’s most famous ‘names’ actually blends of varieties?

Did you know for example that the great wines of Bordeaux are blends, as is Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Some of Italy’s great red wines: Amarone and Chianti are other good examples, not forgetting Spain’s greatest export Rioja, the fortified and still wines of the Douro in Portugal, and (arguably the most famous and prestigious of them all) Champagne.

So why blend varieties?

Different grape varieties have different qualities

This is undoubtedly the main reason. All grapes have different physical attributes – by which I mean, acidity, fruit, aromatics, tannin, body, etc. Some are more neutral in flavour but have great structure and length, others have incredible aromantic intensity but lack body and tannin. For this reason many grapes work best as blending partners rather than as single varietal wines, it’s the combination of the best attributes of a number of grape varieties that producing such compelling wines.

Climatic

Its noticeable that most of the great wine blends are from Europe. This is by design rather than coincidence. The vagaries of climate in any given vintage (particularly in more marginal growing regions such as Bordeaux and Champagne) could see growers lose their entire harvest if they relied on a single variety. By planting a number of different varieties, each with different growing cycles (budding, flowering, ripening), a particularly bad climatic event: hailstorm or frost, may mean even if one variety fails, the grower has the fallback of other varieties. In essence then, blends came about as a result of growers looking for an insurance policy!

It also helps with logistics, with grapes ripening at different times, winemakers can better plan their production schedules thus preventing logistical nightmares.

History and Tradition

Even with global warming negating the issue of marginal climates, many regions continue to plant the same mix of grapes that originally brought fame to a region with appellation laws dictating which grapes are allowed. It’s no surprise then that most of the world’s most successful blends feature grapes that grow well in similar conditions.

Latterly, more appellations are looking to expand the varieties permitted, to negate the risk of global warming – by planting warmer climate varieties in place of the traditional cooler climate grapes.

Encouraging sales

A less obvious but no less important reason for grape blends is to help promote sales. Winemakers making wines from indigenous varieties that are less familiar than mainstream international varieties will often struggle for visibility and traction in a crowded market. It’s human nature that consumers are risk averse and less likely to take a chance on a wine made from a variety they have never heard of. The answer for many winemakers is to include an international variety in the blend and, more importantly, on the label, in the belief that consumer recognition will encourage sales.

The grapes behind some of the world’s most famous blends:

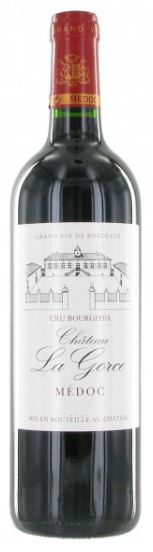

Bordeaux

Red Bordeaux has six permitted grapes: Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Petit Verdot, Malbec and Carmenère, although in reality, most red Bordeaux is a combination of the two Cabernet’s and Merlot, and depends on which side of the Gironde river the wine comes from. For example, left bank Medoc is dominated by Cabernet Sauvignon, the right bank by Merlot with Cabernet Franc the filler. The Cabernet’s providing structure, herbaceous notes, and peppery savouriness to the fleshy Merlot.

Dry White Bordeaux is predominantly a blend of Semillon, Sauvignon Blanc with a drop of Muscadelle, although small quantities of Sauvignon Gris, Colombard, Ugni Blanc and even Merlot Blanc can be used. For the sweet wines of Sauternes, Semillon is particularly susceptible to noble rot, Muscadelle adds aromatics and Sauvignon Blanc, provides the naturally high levels of acidity. It’s all about the balance!

Châteauneuf-du-Pape

Most wine consumers have heard of the Southern Rhone’s most well-known appellation, but how many know the names of the 18 different varieties that are permitted in the appellation? For example: Red Châteauneuf-du-Pape is usually dominated by Grenache, supported by Syrah and Mourvèdre (which thrive in particularly warm climates), with Cinsault and lesser known varieties such as Terret Noir, Picpoul Noir also allowed.

For white Châteauneuf-du-Pape, varieties include Bourboulenc, Roussanne, Clairette, Picpoul and Grenache Blanc – hands up how many of you have heard of these?!

Amarone

One of Italy’s most famous red wines made from partially dried grapes producing hefty, concentrated and richly flavoured wines. Otherwise known as Amarone della Valpolicella, this wine is a blend of varieties little known outside of the region: Corvina, Corvinone, and Rondinella, with Molinara and Oseleta also permitted. The perfume and flavour is driven by the Corvina, with Corvinone providing deeper colour, smoky tobacco notes and higher tannins.

Chianti

Although the Sangiovese is the dominant grape in this blend adding high acidity and bright cherry fruit, Chianti is permitted to include a dizzying number of native varieties including Colorino, Canaiolo, Ciliegiolo and Mammolo, indeed, up until recently some were even white varieties! The blend components has continued to change over time and today some of the red Bordeaux grapes are also permitted in small quantities as are 100% Sangiovese wines.

Super-Tuscans (ie Ornellaia and Tignanello)

The Super-Tuscans came about as a result of a rebellion against perceived antiquated wine laws in Chianti. These wines are more muscular, and full bodied than Chianti with a dark fruit profile thanks to international varieties Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, and Cabernet Franc alongside the native Sangiovese.

Rioja

Although the base of red Rioja is Tempranillo, permitted grapes include Grenache (known locally as Garnacha), Mazuelo (aka Carignan) and Graciano adding body and spicy fruit, colour, and structure respectively. White Rioja allows up to 8 grapes, with Viura the most widely used – it’s high yielding and acidic but fairly neutral in flavour so grapes such as Malvasia and Garnacha Blanca add aroma, fruit, and texture to the blend.

Champagne

Arguably the most famous sparkling wine in the world, Champagne is predominantly made from a combination of Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Meunier (Pinot Meunier), although in total 7 varieties are permitted, including Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc. Located at the margins of cool climate winemaking, historically, the grapes planted were the ones considered most likely to ripen, and planting grapes that ripened at different times was crucial. Each variety adds a component to the blend, the Chardonnay providing elegance and acidity, the Pinot Noir, structure, and body and Meunier soft, juicy fruit.

So the next time you reach for a bottle of your favourite tipple, consider for a moment how meticulously the winemaker has crafted his blend! The next Wine Demystifier case will include a few of the wines I’ve mentioned, as well as some other intriguing blends from across the globe. Look out for more details coming soon.